In most cases, pianists customarily perform concertos using the composer’s own cadenza, providing that such materials exist. This is not the case for some of Mozart’s later piano concertos, as no original copies of his cadenzas is known to have survived. What next? Choose one that has already been written by an equally capable composer, or… attempt to write one themselves? In this blog I will explore these ideas with referring to examples of cadenzas of Mozart’s piano concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466.

What is a good Cadenza?

Well, the sole purpose of a cadenza is to excite and astonish the audience. Cadenzas are not on a measure of the soloist’s virtuosity, but moreover, their wit. As said by the Eighteenth-century theorist Daniel Gottlob Türk, a cadenza does not ‘have to be erudite, but novelty, wit, an abundance of ideas and the lie are so much more its indispensable requirements’.[i] Johann Joachim Quantz, almost forty years the predecessor of Türk, aligned musical wit with the ability to take risks, and invoke imagination: ‘Because of the necessity of speedy inventions, cadenzas require more fluency of imagination than erudition’.[ii]

Thus, musical wit is personal; in Mozart’s time, composing cadenzas were a common practice. There is an element of surprise, newness, and so music needs to feel like it was made on the spot, and if it was prewritten, the act of composed improvisation memorised by the soloist should give no hint of its pre-existence during the concert. Türk summarised this in this predicament in a humorous manner:

‘To be sure, a cadenza is often first invented during the performance, and if it succeeds, the player receives so much the more applause. But this enterprise is too risky, and one should not count on such a happy coincidence when playing for a large audience… […] whether the player is making up the cadenza at the moment or has already sketched it beforehand is not going to be obvious to the listener anyway…’[iii]

For Mozart’s earlier concertos, he did write out some of his cadenzas, and these were published by Johann Anton Andre in 1804 under the title Cadences ou points d’orgue pour pianoforte.[iv] Yet, Mozart seem to have guarded against others using his cadenzas: in a letter to his father on 23rd March 1782, he asked his father to guard his cadenza written for concerto in D major ‘like a jewel – and not to give it to a soul to play… I composed it for myself and no one else but my dear sister must play it.’ Similarly, in this portfolio of cadenza manuscripts, he was specific in naming the identifying of performers. Hence, Mozart expects pianists to create their own cadenzas.

But how? Both Quantz and Türk have outlined sets of instruments for writing out cadenzas, and also inform expectations of composing improvisations. In particular, Türk’s treatises on School of Clavier playing enforced on rules for writing pianoforte cadenzas.[v] My top 3 favourite rules are: 1) Length – not long; 2) Unexpected and surprises added – appropriately; 3) No idea should be repeated in the same key or other, no matter how beautiful it may be.

Türk didn’t quite set enough boundaries for us to be on the right track to create the Mozart-archetype cadenzas…. But I guess we could have look at a few examples of how others have taken a stab at it, particularly the cadenza for Mozart’s piano concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466.

It is unlikely that Mozart wrote out cadenzas for this work. Preparations for the premiere of the concerto on 11th February 1785 was on fine cutting edge; so rushed that the copyist was still working on the orchestral part as audiences were arriving for the concert.[vi] Mozart simply had to improvise on the spot. As the concert was part of a subscription series (called the Academie) in which Mozart introduced his music to his patrons, it is unlikely that Mozart would have repeated this item in the subsequent concerts; after all, his extensive compositions were awaiting recognition.

Many composers and virtuosos especially in the nineteenth century have taken initiative to creating their own cadenzas to complete the performance of the Concerto in D minor, including Ludwig van Beethoven, Clara Schumann, Johann Brahms and Ferrucio Busoni. Amongst them, the Beethoven version cadenza is the favourite amongst pianists today: Murray Perrahia, Mitsuko Uchida, Sviatoslav Richter and Martha Argerich. Here’s Uchida playing the cadenza:

Mitsuko Uchida, Piano & Conductor Camerata Salzburg [1998 Mozartwoche Salzburg]

In every respect the cadenza reflects Beethoven’s genius. The exploration of the modulatory route (from the cadential six-four to the announcement of the theme in B major) via a chromatic descent is full of adventure and wit. The theme introduced in B major is coloured in contrast by its echoes in the minor key. Using part of the theme Beethoven elevates the motif via sequential development, only slightly, before sinking back into the resemblance of the opening call to the concerto in g minor. This transits into introduce another theme from the concerto, this time simply just recalling the theme as it is. The cadenza ends with the burst of swift virtuoso in Più Presto, then at the signal of the cadential trill the left hand echoes the last 3 notes of ascension of the d minor harmonic scale to direct the orchestra back in.

Truly a work of genius; nothing of the cadenza itself can be criticized. However, taken into the consideration the rules by Türk, Beethoven was not so obedient in doing what is stylistically correct: too long; too many surprises and wit; too many repetitions of beautiful themes. It was, as Arthur Hutchings complained, ‘a piece within a piece’ that tends to distract from the unity of the movement as a whole.[vii] Despite the danger of the cadenza being standing as a piece of its own, there is the undeniable authority of Beethoven being of all composers the one with the closest associate links with Mozart, and that this finesse work finds nothing of more equal worth: hence, many concert pianists today chose to perform Beethoven’s cadenza rather than others or perform their own.

There are some pianists who have created their own cadenza versions. Malcolm Bilson’s recording with John Elliot Gardiner, for example, stands as one being most ‘stylistically correct’ (according to Türk’s standards). It is logically coherent, both in terms of form and balance between thematic material and harmonic embellishment. The length is relatively short and concise, few key changes, brief encountering of the theme, followed by swift sequential development leading to the cadential trill.

Malcolm Bilson with Sir John Eliot Gardiner and the English Baroque Soloists [1987 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Berlin]

It is pretty good, – but if I were to choose, I think I still prefer Beethoven’s cadenza, in spite of the reasons of the imperfections of the Beethoven. But can there ever be a most perfect cadenza for all? According to Donald Francis Tovey, the D minor concerto was ‘the most famous, the most perfect, and if so disputable a term be worth risking, the greatest of all Mozart’s concertos’.[viii] Could another cadenza written by one other than the composer ever match the same perfection as Mozart exerts in this cadenza? Or do we agree with what Mozart scholar Alfred Einstein say, that ‘beyond which no progress was possible, because perfect perfection is imperfectible.’[ix]

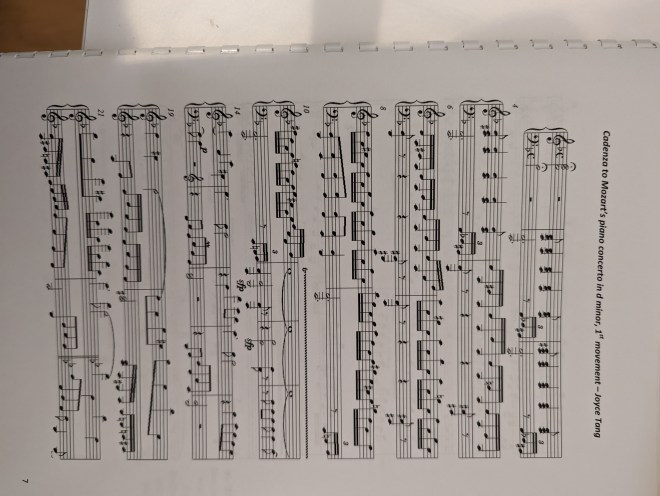

Perhaps perfection can be achieved when one performs side-on with the composer himself: dare you to write your own cadenza.

Postlude: one of my personal favourites: Alfred Brendel with Sir Charles Mackerras and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra [1999 Universal International Music B.V.]

Ruiter-Feenstra, P. Mozart cadenzas. [Unpublished]. Swain, J. P. (1988). Form and function of the classical cadenza. The Journal of Musicology, 6 (1), 27–59. Retrieved May 5, 2009, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/763668 Tromlitz, J. G. (1991). The virtuoso flute player (A. Powell, Trans.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Türk, D. G. (1982). School of clavier playing (R.H. Haggh, Trans.). Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. (Original work published 1789)

[i] D. Mirka (2005) ‘The cadence of Mozart’s cadenzas’, The Journal of Musicology, 22 (2), 292–325. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4138360.

[ii] J. J. Quantz (1752). On playing the flute, 2nd ed. E. R. Reilly translated in 2001, 157.

[iii] D.G. Türk (1789). Clavierschule, (R.H. Haggh, Trans. 1982) School of clavier playing, Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 297.

[iv] https://imslp.org/wiki/Category:Andr%C3%A9%2C_Johann_Anton.

[v] D.G. Türk (1789). Clavierschule, see endnote 3.

[vi] M. Steinberg (1997). The Concerto: A Listener’s Guide. Oxford, 303-305.

[vii] A. Hutchings (1948). A Companion to Mozart’s Piano Concertos. Oxford University Press, 206.

[viii] P. Gutmann (2008). ‘Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Piano Concerto # 20 in d minor, K. 466’, http://www.classicalnotes.net/classics3/mozart466.html, quoting D. F. Tovey (1939) Essays in Musical Analysis. Oxford.

[ix] P. Gutmann (2008). ‘Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Piano Concerto # 20 in d minor, K. 466’, http://www.classicalnotes.net/classics3/mozart466.html, quoting A. Einstein (1945) Mozart – His Character and His Work. Oxford.

Hi Joyce, lovely blog here! I think this topic is really rich food for thought. Sometimes when we reproduce set cadenzas – either because they are now part of the canonical transmission of a work or because of simple habit – I think we move further away from the true purpose of a cadenza, which was also a mini window into the performer’s take on the work through improvisation. Composed cadenzas are interesting too – I wonder if we know for sure what Beethoven really felt about his cadenza for the D minor Mozart concerto being so intrinsic a part of the work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes Anisha! The delight of cadenza is that it is the place for the soloist to take the spotlight, and pre-19th century this was rare as the concept of a ‘virtuoso’ has not yet formed (perhaps a topic for the next post!). Retrospectively, we now have the virtuoso – and have to maintain that statue, especially in a cadenza!

In regards to Beethoven – not sure about what he thought, but when his cadenza first appeared, it was not well received; for example, in the Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode, it was criticized for similar reasons as what Hutchings outlined. Also, it was not until 1864 where in Breitkopt & Härtel Gesomtausgabe that these Beethoven cadenzas were ‘approved’ in print. And even in 1933, Friedrich Blume, giving the Beethoven cadenzas in the appendix for the Eulenburg miniature score, praised them as “die meisterhaftesten, die dennoch leider selten benutzt warden” (This masterly mannered writing, unfortunately nevertheless have became rarely used”). So, before 1933, pianists still rarely used the Beethoven cadenza! Sad that we don’t have much recordings available to hear many different versions.

LikeLike

Thanks for this, Joyce – this is now getting more interesting than the main blog itself for me!

What is most interesting about the process through which certain cadenzas get embedded in the transmission process is their appearance in print. Works almost the same way in how a certain translation of an opera in vernacular became the accepted version oft times.

I am reminded of the violinist Gilles Apap’s cadenza in the third movement of KV216: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=gs1HW2w203Y

Hopefully some food for thought later on about what Mozart’s or Beethoven’s cadenzas on stage might have been.

A

LikeLiked by 1 person