There was a call for papers which caught my eye back in August. I have a rough idea of what I would like to present on, but have not got around to writing the proposal. The deadline is November 1st, so I should really get on with it. This blog serves as a reminder about the kind of perspective of approaching writing conference proposals, so to write a proposal that is compelling and engaging.

What makes a conference proposal (or abstract) stand out? LSE’s blog on writing a killer conference abstract regards conference abstracts as a kind of ‘sales tool’: selling ideas to conference organisers, then to conference delegates. Having the right pitch is important: the idea has to be unique, but fascinating and relevant to others at the same time. Their blog outlines some questions to think over before crafting a proposal:

What kinds of presentations is this conference most likely to attract?

How can you make your presentation different from others, and appealing?

Clues to answering these questions may be found in the call for papers themselves. In each conference, whilst there may be only one overarching theme, there are usually multiple categories / methodological approaches to unpacking the theme. In one’s research, particularly if it is an extended-period project, it is quite easy to find common grounds with several of the outlined categories. The difficulties lies in that you only have 20-ish minutes for your presentation: that is not enough to talk about 2 or more years of research findings. It is up to us to narrow the focus. The history department from the NC State University believes that one question is enough to answer for a conference paper: ‘Too many questions takes up too much space and leaves less room for you to develop your argument, methods, evidence…’

How then should one decide what to focus on? In my situation, my dilemma was to whether submit an abstract for a conference paper or lecture recital. In the latter, one is expected to give a mini-performance as evidence, along with evidence from other sources to spell out a conclusion. I am a strong advocate for including sound samples in music-conference papers, so the questions for myself were ‘how much music am I planning to demonstrate on the piano’, and ‘how much time would it take to explain key concepts of what I am doing on the piano in order for others to follow’. Answering these questions eventually helped me to decide to submit an abstract for a conference paper: I only wanted to demonstrate one piece on the piano, and that in itself was not entirely the crux of the argument; it was more of a novelty.

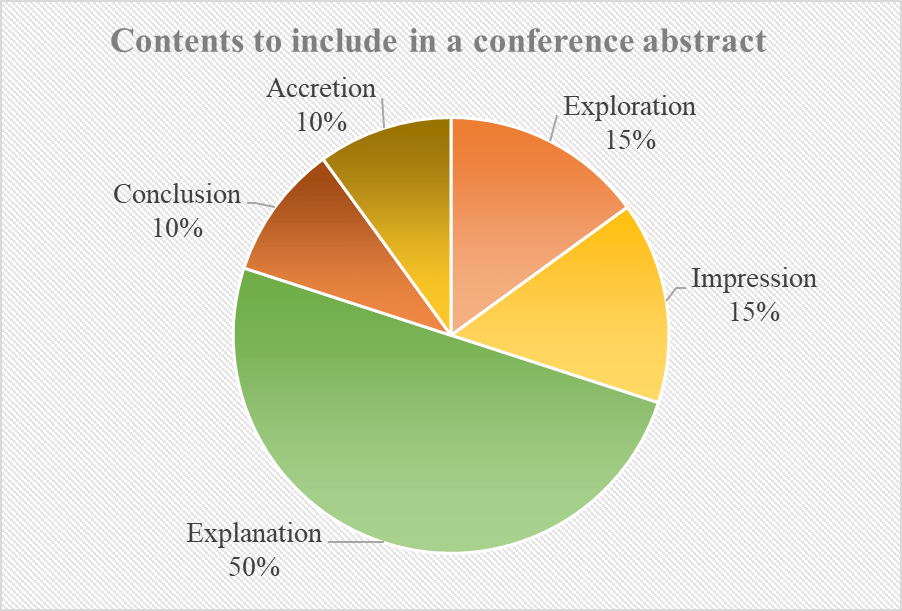

Having thought about conference audiences, the fashionable topics, and your own topic, drafting the abstract is then a matter of refining eloquence and articulacy in writing. Practice is key. One advice from my supervisors was to read A LOT of abstracts from different conferences and grants / fellowships award holders, so to get a gist of the kinds of content good abstracts contain. My summary so far is that good abstracts should definitely contain a catchy title; afterwards an abstract addressing 5 points: exploration, impression, explanation, conclusion, and accretion.

In Exploration you are defining the research field and what others have done. Leaving an Impression is telling others what your unique approach is to this field of research. Explanation is showcasing your selection of sources and how you have analysed them. Give a brief summary of key findings in your Conclusion. And finally, Accretion, the impact made or value added to the field.

Whilst there may not be any ‘golden ratio’ between the 5 points, I conclude this blog with the following chart showing the trends amongst what I consider are well-written abstracts.