Sieh dich tüchtig im leben um, wie auch in anderen Rünften und Wissenschaften.

“Look deeply into life, and study it as diligently as the other arts and sciences.” – Robert Schumann[i]

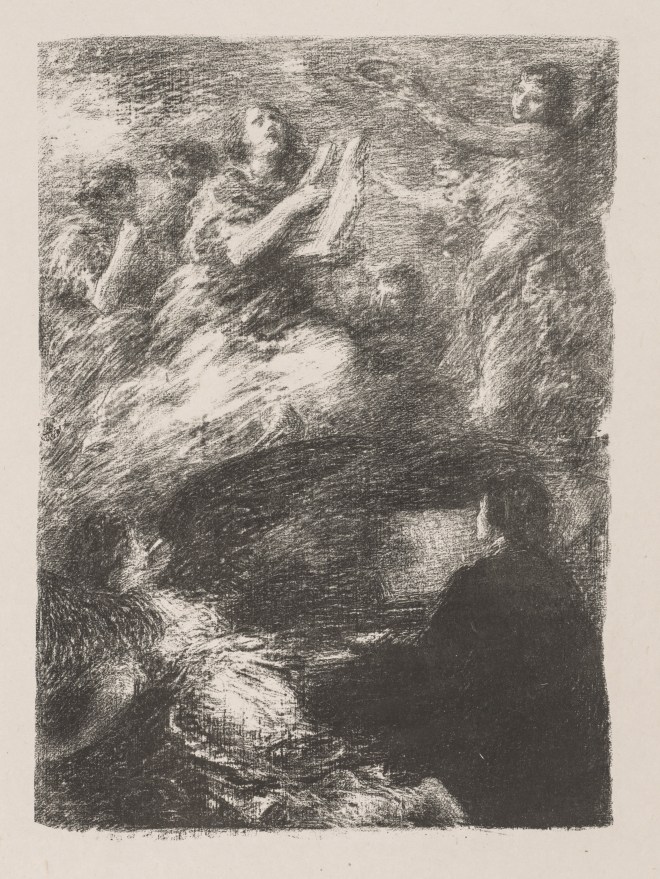

Last Theme of Robert Schumann by Henri Fantin-Latour (French, 1836-1904) is licensed under CC-CC0 1.0

Robert Schumann has always been one of my role models. A somewhat eccentric genius, Schumann played (the piano), critiqued insightfully (about music), and romanced a stunning wife (Clara Schumann). Pouring out stoic emotions about life, Schumann’s compositions are a reflection of a musician in deep thought. Confronted with depression, Schumann’s life ended short at age 46, but his music and words lived on.

One can argue that all composers and musicians are deep thinkers and overtly emotional by nature, which can be felt and heard through their music. What makes Schumann stand out from all else? In my own practice, I like playing Schumann, but not to the extent of love. And despite his A-minor piano concerto being one of my all-time favourite pieces, his compositions seldom feature on my Spotify playlist. So why Schumann?

My high regard of Schumann began in my Academy years. After playing his Abegg variations, I went on to learning his 2nd piano sonata (G minor, Op. 22). My piano professor was quoting Schumann sayings, and out of curiosity I asked him where he was getting all this stuff from. This led to a finding of Schumann’s book On Music and Musicians,[ii] which, thinking about it now, was probably the initial spark to why I want to learn to communicate the message of music through speech and writings.

On Music and Musicians is a book much like proverbs in the bible: phrases or paragraphs of golden wisdom. The book is not in a chronological order, but rather a translated compilation of Schuman’s articles and observations on musicians. There are other complications like such kind, such as Schumann on Music: A selection from the writings,[iii] and Robert Schumann’s Advice to Young Musicians,[iv] but they all originate from ‘blogposts’ in Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, the German press founded by Schumann himself in 1834.

Schumann’s expressing of his opinions were lucidus and thorough. In some ways, his ‘stories’ seem almost fictional, – Schumann often signed his articles using one of his three pen names: Florestan, Eusebius, and Master Raro. My favourite was reading his adoration for Chopin; on defending the composer against animosity of critics, Schumann furiously wrote:

“Heaven forbid. Milk versus poison, cool blue milk! What is a musical paper compared to a Chopin concerto? What is a schoolmaser’s madness compared to poetic frenzy? What are ten editorial crowns compared to an adagio in the second concerto? And believe me, Davidites, I should not think you worthy of address… even with united effort we cannot hope to attain, but only to kiss the hem of its [the concerto] garments. Away with your musical journals!”[v]

Exaggerated they may be, the writings do reflect a real encountering and thoughts of a nineteenth-century person. Schumann’s articles not only gave information but also gave the information life. So often, musicologists are criticised by performers that their writings are too academic and have no relevance to music itself; according to the conductor Thomas Beecham, musicologists are not musician: “a musicologist is a man who can read music but can’t hear it.”[vi] Schumann has shown that it doesn’t have to be like this. He advocated that music studies speaks life from one to another, and that a musician’s vanity and self-adoration can be cured through ‘the study of the history of music and the hearing of master-works of different epochs’.[vii] Knowledge about the past enriches one’s interpretation, and these intertwined with present-day experiences make music live on for the future.

[i] Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Bd.XXXII, Nr.36 (May 3, 1850).

[ii] Schumann, Robert (1982). Wolff, Konrad (ed). On Music and Musicians. Translated by Paul Rosenfeld. University of California Press.

[iii] Schumann, Robert (1965). Pleasants, Henry (ed.). Schumann on Music: A Selection from the Writings. New York: St Martin’s Press.

[iv] Schumann, Robert (1850). Advice to Young Musicians. Translated by Henry Hugo Pierson. Leipzig & New York: J. Schubert co.

[v] On Music and Musicians, 130.

[vi] Proceter-Gregg, Humphrey (1976). Beecham Remembered. London: Duckworth, 154.

[vii] On Music and Musicians, 34.